For most people, paying estimated taxes is a fairly straightforward affair. The IRS expects four equal payments throughout the year, simple as that. But what happens when your income isn't so simple?

This is a common headache for early retirees. The standard method often creates a serious cash flow crunch if your income is lumpy or unpredictable.

The annualized income installment method is the solution. Think of it as a "pay-as-you-go" tax strategy that lets you make estimated tax payments based on the income you actually earn each quarter, rather than a rigid, predetermined amount.

Matching Your Tax Payments to Your Cash Flow

For early retirees, trying to pay estimated taxes on an unpredictable income stream can feel like trying to pay a variable utility bill with a fixed budget. The standard IRS approach just doesn't work when your earnings don't arrive in four neat, equal chunks.

This is exactly where the annualized income installment method shines. It ditches the rigid structure, allowing you to sync what you owe the IRS with what you've actually brought in during a specific period. For the 72tProfessor.com community, this is a game-changer.

Why Is This Method Ideal for Early Retirees?

While a Substantially Equal Periodic Payment (SEPP) plan gives you a steady, predictable base, many early retirees supplement that income with other, more volatile sources.

You might be dealing with:

- Capital Gains: A big, one-time income spike from selling stocks or real estate.

- Freelance or Consulting Work: Side project income that often arrives in irregular chunks.

- Seasonal Business Income: Earnings that are heavily concentrated in just a few months of the year.

If you're stuck on the standard payment plan, you could easily find yourself overpaying the IRS during lean quarters, only to get slammed with an underpayment penalty when your income surges later on.

Avoiding Underpayment Penalties

The annualized method is your best defense against those penalties. For anyone planning an early retirement before age 59½, using IRS Form 2210, Schedule AI is a smart way to shield yourself from underpayment penalties on uneven income streams.

The numbers don't lie. IRS statistics for 2022 show that 2.4 million taxpayers filed Form 2210. Of those, 18% used Schedule AI to wipe out penalties that averaged a painful $450—saving those filers over $200 million collectively. You can dive into the details by reviewing the official instructions for Form 2210 on the IRS website.

This method is not just about avoiding penalties; it's about maintaining financial control. By paying taxes only on the income you've received, you keep more of your money working for you throughout the year, ensuring smoother cash flow and greater peace of mind.

This approach syncs your tax obligations with your financial reality. It’s a proactive strategy that works hand-in-hand with other retirement income tools, like knowing the ins and outs of proper tax withholding codes to manage your SEPP distributions effectively.

Standard Method vs Annualized Method at a Glance

This quick comparison shows the key differences between the two primary ways to calculate estimated taxes and helps you decide which is right for your financial situation.

| Feature | Standard Estimated Tax Method | Annualized Income Installment Method |

|---|---|---|

| Payment Structure | Four equal quarterly payments. | Payments vary based on income earned in each period. |

| Calculation Basis | Based on the previous year's total tax liability. | Calculated based on income and deductions as they occur. |

| Best For | Stable, predictable income (W-2 wages, pensions). | Uneven or seasonal income (freelancers, investors, retirees). |

| IRS Form | Not required if you pay on time. Form 2210 if penalty applies. | Requires filing Form 2210, Schedule AI with your tax return. |

| Main Advantage | Simple and easy to calculate. | Avoids overpayment and underpayment penalties with fluctuating income. |

| Main Disadvantage | Can cause cash flow issues if income is uneven. | More complex calculations and requires diligent record-keeping. |

Ultimately, the choice depends on your income patterns. If your earnings are consistent, the standard method is fine. But if you're navigating the variable income streams common in early retirement, the annualized method is an indispensable tool for financial stability.

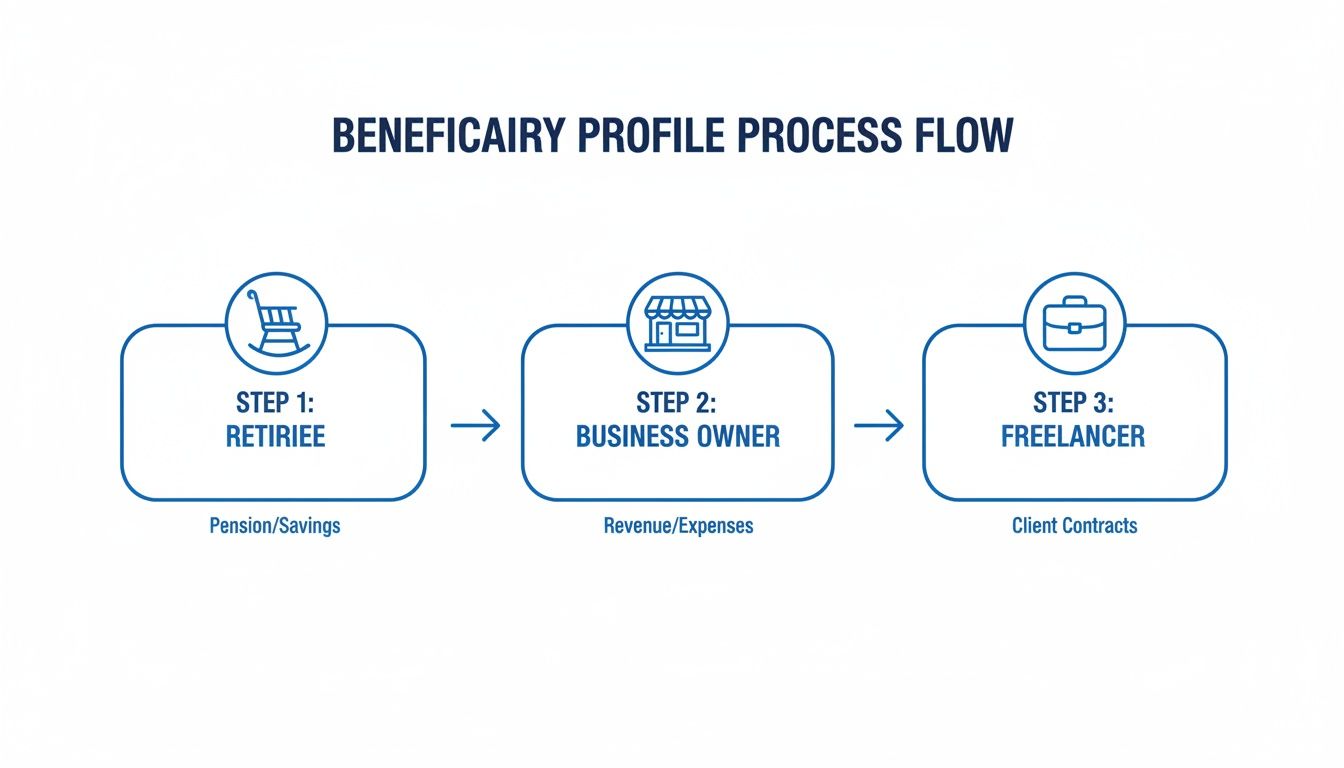

Who Benefits Most From This Tax Strategy?

The standard way of paying estimated taxes—four equal payments—works just fine if you have a predictable W-2 job. But for anyone whose income isn't so steady, that one-size-fits-all approach can create a real financial headache. The annualized income installment method isn't for everyone, but for the right person, it's a game-changer that makes your tax payments match your actual cash flow.

This strategy is basically built for people whose income doesn’t arrive in four neat, equal packages. Instead of trying to cram your fluctuating earnings into a rigid payment schedule, this method lets your tax payments rise and fall right along with your income. That flexibility can be a lifesaver.

The Early Retiree with Diverse Income Streams

Let's picture the typical early retiree. They've set up a 72(t) SEPP plan, which gives them a reliable, steady stream of income each month. But their financial life is often more complex than just that one income source.

Maybe they decide to sell a big chunk of appreciated stock in the second quarter, creating a significant capital gain. A few months later, they might sell a rental property, leading to another spike in income. If they were stuck with the standard method, they'd have to make large, equal tax payments starting in Q1—potentially draining their cash reserves long before they ever saw that money from the sales.

The annualized income installment method solves this problem perfectly.

- Q1 Payment: Based almost entirely on their 72(t) distributions, their first tax payment is small and easy to manage.

- Q2 Payment: After selling the stock, their payment for this period jumps up to cover the tax hit from that capital gain.

- Q3 & Q4 Payments: Their payments adjust again to account for the property sale and their ongoing retirement distributions.

This approach keeps the retiree from having to sell other investments or mess up their financial plan just to pre-pay taxes on money they haven't even received yet. It creates stability and protects their cash flow.

The Seasonal Business Owner

Now, think about a seasonal business owner—someone who runs a landscaping company in a place with cold winters or owns a beachside shop in a tourist town. Their income is almost entirely packed into just a few months of the year.

For this entrepreneur, over 80% of their annual revenue might pour in between May and September. Come winter, business grinds to a halt. The standard method would demand a huge tax payment in April, precisely when their cash flow is at its lowest. This could easily force them to take out a loan or pull from personal savings just to keep the IRS happy.

By using the annualized method, their tax payments follow their business cycle. A tiny payment is due for the slow first quarter, while the big payments line up perfectly with their peak earning season in Q2 and Q3.

The Freelance Consultant and Gig Worker

Finally, let's look at a freelance consultant. Their world is defined by large, irregular project payments. They might land a major contract and get a $50,000 check in February, but then have nothing substantial come in until another project wraps up in October.

For individuals with lumpy income, the annualized method acts as a financial shock absorber. It eliminates the need to predict the entire year's income with perfect accuracy, allowing for real-time adjustments as circumstances change.

Without this method, the consultant faces a tough choice: make a massive overpayment in Q1 just to be safe, or risk getting slammed with an underpayment penalty later. The annualized approach gets rid of the guesswork. Their Q1 payment covers the tax on that first big check, but if no new income arrives, their Q2 and Q3 payments can be minimal. For anyone navigating the gig economy, that flexibility is absolutely essential.

For early retirees, understanding these scenarios is crucial. While a SEPP provides a stable income base, many have other financial ventures on the side. This method is a critical tool that works alongside your core retirement strategy, protecting your financial stability by making sure your tax obligations never get ahead of your actual cash flow. Exploring these and other alternative tax strategies for retirement can give you an even greater degree of control over your financial future.

How to Calculate Your Payments Step by Step

Knowing the theory is one thing, but seeing the annualized income installment method in action is where it really clicks. Let's walk through the numbers step-by-step to see how it works in the real world. We'll follow an early retiree named 'Alex,' whose financial situation is a perfect example of why this method is so powerful.

Alex's income stream is choppy—a common scenario for people who leave the 9-to-5 world behind. He has some steady retirement distributions, some freelance income that comes in chunks, and a one-time capital gain from selling stock. By breaking down his year, you'll see how his estimated tax payments rise and fall right along with his cash flow. This keeps him penalty-free without putting a squeeze on his budget.

This approach isn't just for early retirees. As you can see, it's a valuable tool for anyone with an unpredictable income.

Whether you're a retiree like Alex, a seasonal business owner, or a freelancer, the annualized method helps you manage your tax obligations far more effectively than the standard, one-size-fits-all approach.

Meet Alex and His Financial Year

To make this tangible, let's get to know Alex's finances. He's single, under 50, and plans to take the standard deduction.

His income for the year is anything but consistent:

- 72(t) SEPP Distributions: He draws $10,000 at the start of each quarter for a total of $40,000.

- Freelance Income: A big project paid out $20,000 in March (Q1).

- Capital Gains: He sold a long-held stock in August, realizing a $50,000 gain (Q3).

If Alex used the standard estimated tax method, he'd have to make four identical, large payments. That would create a real cash crunch in the months he earned less. Instead, he’s using the annualized income installment method, which he'll calculate on Form 2210, Schedule AI.

The Core of the Calculation: The Annualization Factors

The real magic behind this method comes from the IRS's annualization factors. These numbers are simple multipliers that take the income you've earned so far and project it out as if you earned it at that rate for the whole year. This lets you calculate tax based only on money that's actually hit your bank account.

Here are the factors for each payment period:

- First Period (Jan 1 – Mar 31): Factor is 4

- Second Period (Jan 1 – May 31): Factor is 2.4

- Third Period (Jan 1 – Aug 31): Factor is 1.5

- Fourth Period (Jan 1 – Dec 31): Factor is 1

Now, let's plug Alex's numbers into the formula for each quarter.

Quarter 1 Payment Calculation (Due April 15)

First, we tally up Alex’s income received between January 1 and March 31.

- 72(t) Distribution: $10,000

- Freelance Income: $20,000

- Total Q1 Income: $30,000

Next, we use the first period's annualization factor (4) to project this out for a full year.

Formula: (Income for the period) x (Annualization Factor) = Annualized Income

Alex's Calculation: $30,000 x 4 = $120,000

Alex then figures out the tax on this $120,000 annualized income (after his standard deduction). For this example, let's say his total projected tax comes to $18,000. To get his required Q1 payment, he multiplies that by 22.5% (the required installment percentage for the first period).

His required payment for Q1 is $4,050. He pays that by the April 15 deadline.

Quarter 2 Payment Calculation (Due June 15)

For the second period, which covers everything from January 1 through May 31, Alex only had one new item of income: his next $10,000 72(t) distribution.

- Cumulative Income (Jan 1 – May 31): $30,000 (from Q1) + $10,000 = $40,000

- Annualized Income: $40,000 x 2.4 (Q2 factor) = $96,000

Because his annualized income dropped, so does his projected tax. Let's say the tax on $96,000 is $12,500. The required cumulative installment for this period is 45% of that total tax, which comes out to $5,625.

But wait—he doesn't pay that full amount. He's already paid $4,050. So, his actual payment due on June 15 is just the difference: $5,625 – $4,050 = $1,575. His tax payment perfectly reflects his lower income during this stretch.

Quarter 3 Payment Calculation (Due September 15)

This is where things really pick up. Between June 1 and August 31, Alex got another $10,000 from his 72(t) plan and cashed in on that $50,000 capital gain.

- Cumulative Income (Jan 1 – Aug 31): $40,000 (from Q2) + $10,000 + $50,000 = $100,000

- Annualized Income: $100,000 x 1.5 (Q3 factor) = $150,000

The tax on this much higher annualized income is, unsurprisingly, a lot more. Let's assume it's $25,000. The required cumulative installment for the third period is 67.5% of that tax, totaling $16,875.

To find his Q3 payment, Alex subtracts what he's already paid: $16,875 – $5,625 = $11,250. This large payment is due right after he received his large capital gain, preventing a nasty underpayment penalty down the road.

This principle works for businesses, too. Picture a seasonal retail shop that makes most of its money during the holidays. In 2023, a retailer reported first-quarter earnings of $250,000. Using this method, they multiply that by the factor of 4 to project $1,000,000 for the year. At a 21% corporate tax rate, their estimated tax for that period is based on a $210,000 liability. This IRS-approved approach, outlined in regulations under Section 6655, helps them avoid underpayment penalties that can reach 5-8% annually. To dig deeper into business applications, you can read more about the US estimated tax system.

Final Payment and Reconciliation

When the final payment is due on January 15 of next year, Alex will simply total all his income for the year, calculate his actual tax liability, and subtract the three payments he's already made. That final amount settles his tax bill for the year.

By using the annualized income installment method, Alex perfectly aligned his tax payments with his income. He sidestepped penalties and kept his cash flow healthy—a winning strategy for the dynamic financial life of an early retiree.

Navigating Special Situations and Complex Scenarios

Life doesn’t always follow a neat, predictable path, and neither does our income. When major events pop up, they can create some unique tax headaches. Fortunately, the annualized income installment method is specifically designed to handle these curveballs with precision. For anyone in early retirement facing big financial shifts, getting a handle on this method is a key piece of the puzzle for staying on solid ground.

A standard tax year is simple enough, but what if you're dealing with a 'short tax year'? This can happen for a few reasons, like changing your accounting period, moving out of the country, or in the year of a person's death. When this happens, you can't just plug in the standard numbers; the math has to be adjusted to reflect that shorter timeframe.

This built-in flexibility is crucial for sidestepping penalties during times of change. It makes sure your tax payments are a true reflection of your income, even when your financial year doesn't line up with the calendar.

Handling Unexpected Financial Windfalls

One of the best uses for the annualized income installment method is when you suddenly come into a large amount of money. Imagine you get a big inheritance or cash in on a massive capital gain from an investment late in the year.

If you were using the standard way of paying estimated taxes, that late-year income spike would make it look like you underpaid for the first few quarters. The result? You’d be looking at a shocking tax bill and a painful penalty come April.

The annualized method completely prevents this nightmare scenario.

- Your payments for the first two quarters would have been based on your normal, lower income.

- Then, your third or fourth quarter payment would jump up to cover the taxes on that windfall.

This pay-as-you-go approach means you only pay the tax on that big chunk of cash after you've actually received it. It protects your cash flow and gets rid of the risk of a nasty surprise penalty. Grasping how these distributions are taxed is a critical part of planning. For a deeper dive, check out our guide on whether a retirement distribution counts as income.

The Annualized Method in a Short Tax Year

A short tax year means you have to make some careful tweaks to the calculation periods and the numbers you use to annualize. The main idea is still the same—you annualize the income you've earned up to that point—but the math is adjusted for the shorter timeline.

For instance, if your tax year wraps up after only seven months, the payment periods and multipliers you'd use on Form 2210, Schedule AI, would be different. The IRS has specific rules for these cases to ensure taxpayers aren't hit with unfair penalties.

This adaptability is really the core strength of the annualized method. It recognizes that our financial lives aren't static and gives us a framework to manage taxes accurately through major life transitions, ensuring fairness and preventing a ton of financial stress.

Short tax years can be tricky, but the annualized method, outlined in 26 CFR §1.6655-5, gives both people and businesses the tools to get through them without getting penalized. In one real-world case, a corporation was acquired mid-year on July 31 and had to file for a short termination year. By using annualization, they cut their tax obligations by 45% compared to what they would have paid using the standard method. To see the nitty-gritty details, you can review the official guidance on the Treasury's website.

Whether you're dealing with a one-off financial event or a fundamental change to your tax year, the annualized income installment method provides the structure you need to stay on the right side of the IRS. It turns complex situations that could be tax disasters into manageable, predictable events.

Common Mistakes and Proactive Filing Tips

Knowing the rules of the annualized income installment method is one thing; putting them into practice flawlessly is another challenge entirely. The method’s complexity can lead to simple mistakes that wipe out all its benefits and trigger the very penalties you’re working so hard to avoid.

The good news? Most of these errors are preventable with a bit of foresight and organization. Once you understand the common pitfalls, you can build proactive strategies to keep your calculations sharp, your records clean, and your tax filing smooth.

Let’s walk through how to sidestep those common mistakes and use this powerful tax tool with confidence.

Mistake 1: Messy Record-Keeping

The single biggest source of errors with the annualized method is disorganized record-keeping. It's a simple concept with huge consequences. If you can't prove exactly when you received income or paid a deductible expense, you can’t accurately calculate your annualized adjusted gross income (AGI) for each period.

A casual approach just won't cut it here. You must be able to trace every dollar to a specific date to justify your varying payments to the IRS. Without a solid paper trail, your calculations become guesswork, and an audit could easily disqualify your use of the method.

Proactive Strategy: Keep Meticulous Records

Think of yourself as the CFO of your own finances. The moment income hits your account or you pay a relevant expense, document it.

- Use Accounting Software: Tools like QuickBooks or even a detailed spreadsheet can tag every income and expense item with a date. This makes it simple to pull reports for each of the four payment periods.

- Scan and Digitize: Don't let paper receipts pile up. Immediately scan or photograph invoices, 1099s, and bank statements, and file them in dated folders on your computer or in the cloud.

- Separate Accounts: Consider opening a separate bank account just for your variable income. This creates a clean, chronological record of deposits that’s incredibly easy to track.

Mistake 2: Miscalculating Your Annualized AGI

Even with perfect records, the math itself can be a tripping point. A frequent error is to simply annualize your gross income without factoring in the deductions you're entitled to for that specific period. This rookie move leads to an inflated annualized AGI and an overpayment of taxes.

Another common misstep is applying the annualization multipliers incorrectly or forgetting to use cumulative income from the start of the year for each new period's calculation. Each period builds on the last, and missing this critical step will throw off all subsequent payments.

The accuracy of the annualized income installment method hinges on precision. Each calculation period is a snapshot in time, and your AGI for that snapshot must reflect both the income earned and the deductions paid during that specific window.

Mistake 3: Forgetting to File Form 2210

This is the most critical mistake of all—and a heartbreaking one to make. Even if you calculate and pay everything perfectly throughout the year, you will still get hit with an underpayment penalty if you fail to file Form 2210 with your annual tax return.

Why? The IRS's default assumption is that everyone uses the standard, equal-payment method. Form 2210, specifically Schedule AI, is your official declaration that you chose a different path. It’s the proof that your smaller payments in early quarters were justified and not just a mistake.

Proactive Strategy: Make Form 2210 a Priority

Do not treat this form as an afterthought. It's the key that unlocks the entire strategy.

- Check the Right Box: On Part II of Form 2210, you must check the box (usually Box C) indicating you are using the annualized income method to reduce or eliminate your penalty.

- Attach Schedule AI: This isn't optional. You must complete and attach the full Schedule AI, which shows your income, deductions, and tax calculations for each of the four periods.

- Use Tax Software: Reputable tax software will automatically generate and fill out Form 2210 and Schedule AI based on the income information you enter, making this step much harder to miss.

By steering clear of these pitfalls, you can ensure the annualized method works for you, not against you.

Frequently Asked Questions

Trying to get a handle on estimated tax rules can feel like a maze, especially when your income arrives in fits and starts. The annualized income installment method is a fantastic solution for this, but it’s natural to have a few questions. Let's walk through some of the most common ones.

Getting these details straight will help you figure out if this is the right move for your financial picture.

When Must I Use the Annualized Income Installment Method?

Here’s the simple answer: you’re never required to use it. The annualized income installment method is an optional strategy you can choose if it works in your favor. The IRS default is the standard method, where you make four equal estimated payments throughout the year.

You’ll want to actively choose this method when your income is uneven, lumpy, or seasonal. It lets your tax payments mirror your cash flow, which is a lifesaver. It keeps you from overpaying during lean months or, worse, getting hit with a penalty after a surprisingly good quarter.

Can I Switch Between Methods During the Year?

No, you can't jump between the standard method and the annualized method once the tax year is underway. IRS rules are very clear on this: if you use the annualized method for even a single payment period, you must use it for all payment periods for that tax year.

This means you’ve got to commit to one path at the beginning of the year and follow through. It demands consistent, period-by-period calculations and good record-keeping from start to finish.

The decision to use the annualized method is an all-or-nothing commitment for the tax year. This consistency is essential for accurately calculating your required payments and legally avoiding underpayment penalties.

Because of this rule, it's smart to look at your expected income pattern before the year even starts. If you're anticipating big swings—like selling an investment, a large consulting gig landing, or seasonal business income—opting into the annualized method from your very first payment is the way to go.

What Happens If My Income Is Unexpectedly High in the Last Quarter?

This is exactly where the annualized income installment method proves its worth. If a big, unexpected income event happens late in the year (think a large year-end bonus or a capital gain in December), this method can shield you from retroactive penalties.

Here’s how it plays out:

- Periods 1-3: Your estimated payments would have been calculated correctly based on the lower income you actually earned during those months.

- Period 4: Your final payment for the year (due January 15) will be much larger to cover the tax on that new income.

Since you paid the right amount based on the income you had at the time for each installment, you generally won't be penalized for underpaying in those earlier, lower-income quarters. The method essentially proves to the IRS that your payment history was completely justified.

Is the Annualized Method Only for Individuals?

Not at all. This method isn't just a tool for personal finance. The annualized income installment method is also available to corporations, trusts, and estates that deal with inconsistent income. The core idea is exactly the same: align tax payments with the period when the income was actually earned.

While the specific paperwork is different (corporations use Form 2220, for example), the strategy provides the same critical benefit. It helps businesses, especially seasonal ones, manage their cash flow much more effectively and sidestep underpayment penalties during their slow seasons.

What Is the Safe Harbor Rule and How Does It Relate?

The "safe harbor" rule is another way to avoid underpayment penalties. It's a simpler approach that works by having you meet a specific payment threshold based on your tax bill from the previous year. As a general rule, if you pay at least 100% of the tax you owed last year (or 110% if you're a higher-income taxpayer), you're "safe" from penalties, no matter what you actually owe for the current year.

The safe harbor rule and the annualized method are two separate strategies to achieve the same goal: avoiding penalties. You can use whichever one helps you more. The annualized method is usually the better choice if your current year's income is much lower than last year's, or if most of your income is back-loaded toward the end of the year. It prevents you from having to make huge payments based on a prior, higher-income year that no longer reflects your reality.

Managing your finances in early retirement requires smart strategies that give you both stability and flexibility. A 72(t) SEPP can provide a consistent income foundation, but tools like the annualized income method are essential for handling the complexities of a diverse financial life. At Spivak Financial Group, we specialize in helping you build a comprehensive plan. Learn how you can achieve your retirement goals by visiting us at https://72tprofessor.com.

Spivak Financial Group

8753 E. Bell Road, Suite #101

Scottsdale, AZ 85260

(844) 776-3728